When the local feminist group sounds like the far-right: Femonationalist and Islamophobic messages in Femen-France (Engenderings, LSE)

Published in Engenderings, LSE Gender Department. May 2, 2023.

Femen France claims to be a radical feminist activist group. It was founded in Ukraine in 2008 by Anna Hutsol and, allegedly, Viktor Sviatsky. It is currently led by Inna Shevchenko and is based in Paris. They became internationally recognised after organising semi-naked protests in public spaces; according to their website, the group is formed by “brave topless activists” that use “female sexuality rebelling against patriarchy.”

In this text, I examine the actions of Femen France through an analysis of their Instagram, Facebook and Twitter posts. I argue that the group’s actions can be understood as a femonationalist agenda, whereby feminist ideas and discourses are used for nationalist and xenophobic purposes. Firstly, I analyse how Femen France utilises feminist and LGBTQ+ claims to argue that migrants coming to Europe are sexist and that Western societies, by contrast, are supposedly egalitarian, promoting xenophobic narratives that stigmatise Muslim communities. Secondly, their semi-naked bodies are used to demonstrate a distinctly Western “freedom”; and in doing so, they reject and marginalise women who have different relationships with their bodies. Whether a protester uses their body as a medium is not the only relevant issue, it is also essential where that body is introduced into the public space: this insertion is itself political and has its limitations and significance.

I would like to point out that throughout this text, I reproduce some of the images posted on Femen’s social networks in order to exemplify the type of content they replicate on the networks. I recognise that these images are violent, but I consider it pertinent to point out this violence for what it is without euphemisms. They are uncomfortable and that is why we have to face them. In particular, in the academy of the global North, we have to confront the discourses that the global North produces.

My place of enunciation is rare: I am not Muslim and I am a Mexican woman. I consider myself a feminist although sometimes find myself uncomfortable in feminist circles, especially in Europe and in the US, where I occasionally hear condescending comments about women from Africa, the Middle East and Latin America. I have lived in some “global North” countries for different periods of time. After a couple of months, I get tired of the well-intentioned concerns that turn into racist and stereotypical remarks about what it is to be a “Latina” (a tremendous generalisation of an entire region). I also have French ancestors who migrated to Mexico decades ago. I follow French politics from afar and sometimes I argue with my French relatives and acquaintances about politics. Despite trying “not to take it personally”, whenever a racist remark comes up, I speak out. I am a killjoy during dinner, to borrow a term from Sara Ahmed, and I have made my peace with that.

In 2022, after registering at the French embassy in London, I received the electoral pamphlets for the presidential elections. In her propaganda, Marine Le Pen stated: “I will wage war against Islamism by closing radical mosques” and Eric Zimmour stated: “I will fight the conquering Islam that threatens France, and I will defend our Muslim compatriots who love our country”. I grew up listening to stories of fascist regimes in Europe, exile, anti-Semitism and war. Now I see some of my grandparents’ fears being reflected in how Muslims are portrayed as the enemy in French politics and in some feminist discourses.

It is heartbreaking to realise how the long-term suffragist and feminist fights have sometimes resulted in powerful racist politicians weaponizing their concerns. No woman in French politics has achieved as much as Le Pen. Yet, her figure shows how white women can also oppress other women and consciously or unconsciously perpetuate violence against them and their communities. It is a delusion to think that being a woman is enough to work with a substantive gender agenda; women can also be racist, xenophobic, classist and even misogynist.

The “liberated” body

Femen uses the word “sextremism” to denote their demonstrations. Despite describing it as their invention, the use of naked bodies as media in feminist protests is neither exclusively theirs nor a European-only phenomenon. For example, Sandra Young in ‘Feminist Protest and the Disruptive Address of Naked Bodies’, drawing on Judith Butler’s ideas, shows how in post-apartheid South Africa, activists used their bodies as a strategy to make visible the impact of gender-based violence. The effectiveness of these women’s protests lies in the enforced confrontation with the precarity of the naked and vulnerable bodies which are read as subversive.

Femen use their bodies to communicate their ideas by representing their purported “liberty”. However, this shows a lack of intersectional thinking and dismisses the complexity of the context in which the bodies are inserted during a protest: the same body can be read differently in different spaces. Firstly, what they present as “liberated” is a hegemonic body (white, able, thin, young). Secondly, they intend to contrast nudity against the “suppressed” Muslim women who practice modesty and wear a veil, a feature common to various religions other than Islam. Moreover, the word sextremism can be problematic because it resembles extremism, evoking how Muslims have been portrayed in the mass media (especially since 2001, as Sara R Farris points out), which has generalised all Islamic practices as extremist and recalls the history of Islamophobia in Western culture.

Mariam Betlemidze also considers Femen’s activism as disrupting the flow of traditional processes because it provokes affective reactions in their viewers. The author argues that Femen create “image events”, a concept coined by Kevin DeLuca, referring to staged acts of protest as a tactic, specifically designed for media dissemination. Moreover, the author argues that they create a “gendered dissonance” by occupying public spaces, because “historically, public space has been a domain for masculine actions, while feminine actions were mainly restricted to domestic arenas.” However, I consider that not all public spaces hold the same meaning and that “masculine” arenas are not universal. Furthermore, this becomes problematic when these spaces are also inhabited by migrants from former colonies, or even worse when these areas are formerly colonised countries.

Femonationalist narratives: feminist discourse masks colonial traces

Femonationalism is a concept coined by Farris to describe the attempts of right-wing and neoliberal parties in Western Europe to promote xenophobic policies through the touting of gender equality. According to her, femonationalist discourses portray women as perpetual victims with no agency who need to be saved from Muslim men, an aspect that resembles Femen’s discourse.

Image 1. Inna Shevchenko’s tweet from 2015.

Femen presents the naked body as a western representation of freedom. Their nakedness is weaponised as it is used as a disruption in a racialised context, dragging along a colonial history. This is evidenced by the case of two activists kissing each other in Rabat, Morocco, in 2015, where white French citizens picture themselves as free to experiment with their sexuality in a place formerly colonised by France. Furthermore, it takes place in the Hassan Tower, a symbol of Moroccan independence, a site that houses the mausoleum of King Mohamed V, a national hero against French colonisation. Additionally, they wrote on their torsos: “in gay we trust”, echoing “In God we trust”, the official motto of the US, which is all the more blatant as the US has a long history of meddling in the Middle East and is a prolific promoter of anti-Muslim discourse.

Choosing this location poses two possible scenarios: either their complete ignorance of and disinterest in the Moroccan context led them to carry on their action, or they, as French citizens, consciously decided to stage their image event near the grave of a man who symbolises a counterweight to imperialism. Both are decisions laden with colonial symbolism. Morocco has a penal code that criminalises same-sex relations, a law that has been protested by local activists, like the Aswat collective. Yet, Femen fail to acknowledge Aswat’s work and, likewise, endangers it by fuelling the narrative that women and LGBTQ+ rights demands are a foreign trend. Displaying a lack of interest in building international solidarity networks, protesting against the laws of a country whose context they have no interest in unravelling. Moreover, as Brigitte Vasallo argues, the current penal code itself is a legacy of colonisation, which they have also failed to acknowledge.

When semi-naked hegemonic bodies are used as a medium of protest against oppression, in this case, perpetuated by otherness, any notion of precarity fades. These bodies no longer imply the vulnerability described by Young. Furthermore, this is not the first time that Femen has protested in a predominantly Muslim space. In 2013, for example, they burned a flag with the profession of faith (Shahada) in front of a mosque in Paris, ostensibly in support of the Tunisian activist Amina Tyler, who had actually declared that burning this sacred object was an insult. Moreover, in 2012 and 2014, a group of primarily white topless activists protested in the 18th arrondissement of Paris (a Muslim-conformed neighbourhood) with slogans such as “Muslims, let’s get naked” or “Laicité” (secularism) written on their torsos. It is essential to acknowledge there have been various Femen protests against religious symbols in Europe in recent years, such as Notre Dame Cathedral. Notwithstanding, the strategy of explicitly targeting Islam feeds anti-immigration and other racist ideologies in Europe.

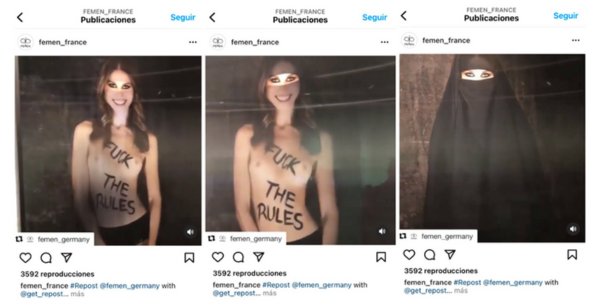

On their website, Femen declare they are willing to combat “dictatorial regimes” as “theocratic Islamic states practising Shari’ah and other forms of sadism”. This statement reflects what Nabil Echchaibi describes as “heavily Orientalised imagery”, that negates the possibility of hybrid Muslim subjectivities with the “reconciliation between Muslim history and culture and the global modernity”. This is also applied to several of their social media releases, such as the video of a thin white woman wearing a niqab that fades out to reveal the sign “fuck the rules” written on her torso.

Image 2. Video posted on Femen French and German Instagram accounts.

When European feminism is self-referential, it falls into condescending attitudes towards women from other regions. It does so by portraying “male Others as sexual threats” and “female Others” as passive victims. Following North African and Middle-Eastern migration to Europe in the 20th century, this rhetoric has intensified. Politicians with seemingly secular ideologies have targeted Muslim communities with a discourse of assimilation, such as France’s 2004 veil ban. As Farris points out, these discourses are exemplified by the anti-Islam rhetoric of far-right parties, with considerable growth in their electorates such as Alleanza Nazionale (Italy), Partij voor de Vrijheid (Netherlands) and Le Front National (France). These political forces are appropriating the feminist and LGBTQ+ rights agenda despite having no real interest in gender equality policies, maintaining the idea of gender equality as a uniquely Western export, as described by Clare Hemmings in Why Stories Matter.

In the French context, the stigmatisation of Muslims and migrants has become central in recent years, with politicians such as Marine Le Pen and Éric Zemmour coming to the fore. Although Femen have published on their Facebook account that they do not support these politicians, there are numerous similarities between their discourse and that of Femen. For example, Le Pen (the runner-up presidential candidate in 2017 and 2022) had a specific section in her electoral pamphlet called “Restore your security and stop immigration”, focusing on “imposing assimilation” of “French values, in particular, secularism;” precisely one of Femen’s constant revindications when they hold signs with the word ‘laicité’ during their protests.

Le Pen also describes herself as a feminist. Yet, she finds “unfair the global accusation and suspicions of men as predators or rapists.” By contrast, she has no problem generalising about Muslim men and, driven by her apparent concern for women’s safety, plans to “wage war against Islamism”. This militaristic rhetoric is also similar to that of Inna Shevchenko, who describes Femen activists as “soldiers” and an “army.” It is also exemplified when Femen members wear military-style boots and step over the flags of Middle-Eastern countries.

FIG. 3 Facebook post from 2019 demanding the liberation of the imprisoned lawyer Nasrin Sodouteh. Many symbols are interconnected, such as the fact that a blonde woman is stepping over an Iranian flag.

Conclusions

When Femen activists use their bodies as media, writing slogans against Islamism and showing their apparent Western freedom by being naked, they demonstrate how limited their discourse is in its lack of intersectional grounding. By rejecting anyone with alternate relationships with their bodies, Femen’s use of white, able-bodied corporeality cements the divide created in their written language between Western purported “freedom” and the Other who fixes and subjugates: migrants and the formerly colonised.

These limitations are exacerbated when they protest at independence monuments, mosques or immigrant neighbourhoods as they normalise a colonial mindset by invading these spaces with their bodies, creating discursive practices that perpetuate xenophobia. Furthermore, it risks legitimising far-right discourses and may endanger activists who defend religious freedom or women’s rights outside the global North, by limiting the notions of feminism uniquely to Western concerns.

Feminists in Europe and mainly white feminists must take responsibility for what they enunciate through their activism. Condescension and racism, disguised consciously or not as a concern for “unliberated” otherness has consequences in media and political discourse that oppress and restrict the rights of other women and their communities. It is necessary to be killjoys even in feminist circles, as Ahmed says: “we have to keep saying it because they keep doing it”. They keep perpetuating neo-colonial, racist and Islamophobic discourses.

Acknowledgements: I would like to thank Yuying Zhu, Marisol García Walls, Juan Carlos Calanchini and Marie Lunau for their fantastic feedback.

Eréndira Derbez (ella/she) is an illustrator and an art historian. She holds a MA and a bachelor’s degree in Art History from Universidad Iberoamericana in Mexico and an MSc in Gender, Media and Culture from the LSE Gender Department. She was awarded the García Cubas prize by the Mexican National Institute of Anthropology and History for her book (co-written with Claudia de la Garza) No son micro. Machismos cotidianos (Penguin Random House, 2020). Twitter: @erederbez